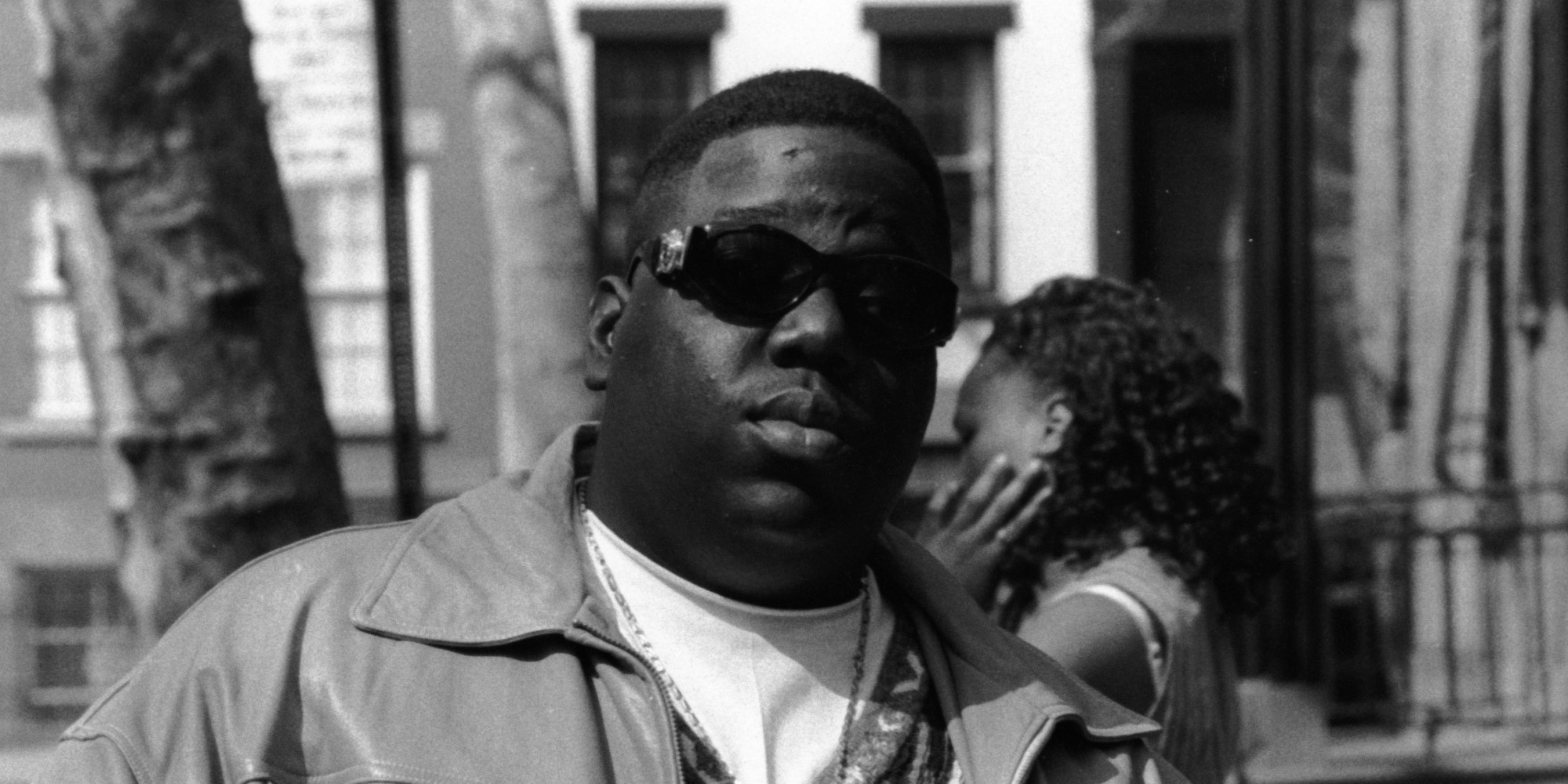

B I G Notorious Death

Attack type, Weapons Blue-steel (exact model and make unknown) Deaths 1 (Christopher Wallace, a.k.a. 'The Notorious B.I.G.' ) Perpetrator Unknown The murder of Christopher Wallace, better known by his stage names ' and 'Biggie Smalls', occurred in the early hours of March 9, 1997. The artist was shot four times in a in, one of which was fatal. Despite numerous witnesses and enormous media attention and speculation, no one was ever formally charged for the murder of Wallace. The case remains officially unsolved, as police have searched for years for more details without success.

In 2006, Wallace's mother, Voletta Wallace; his widow, Faith Evans and his children, T'yanna Jackson and Christopher Jordan Wallace (CJ) filed a $500 million wrongful death lawsuit against the alleging that LAPD officers were responsible for Wallace's murder. Retired LAPD Officer alleged that, the head of, hired fellow gang member Wardell 'Poochie' Fouse to murder Wallace and paid Poochie $13,000. He also alleged that Theresa Swan, the mother of Knight's child, was also involved in the murder, and was paid $25,000 to set up meetings both before and after the shooting took place.

In 2003, Poochie himself was murdered in a drive-by by rival gang members. Contents. Prior events Christopher Wallace traveled to Los Angeles, California in February 1997 to promote his upcoming second studio album, and to film a for its lead single, '. On March 5, he gave a radio interview with on 's, in which he stated that he had hired security because he feared for his safety.

Wallace cited not only the ongoing and the six months prior, but his role as a high-profile in general, as his reasons for the decision. Life After Death was scheduled for release on March 25, 1997. On March 7, Wallace presented an award to at the in Los Angeles and was booed by some of the audience. The following evening, March 8, he attended an after-party hosted by and at the in West Los Angeles. Other guests included, and members of the and gangs. Shooting On March 9, 1997, at 12:30 a.m. , Wallace left with his entourage in two to return to his hotel after the closed the party early because of overcrowding.

Wallace traveled in the front passenger seat alongside his associates Damion 'D-Roc' Butler, member, and driver Gregory 'G-Money' Young. Combs traveled in the other vehicle with three bodyguards. The two SUVs were trailed by a carrying ' director of security. By 12:45 a.m.

, the streets were crowded with people leaving the event. Wallace's SUV stopped at a red light on the corner of Wilshire Boulevard and South Fairfax Avenue just 50 yards (46 m) from the museum. A dark-colored pulled up alongside Wallace's SUV.

The driver of the Impala, a black male dressed in a blue suit and bow tie, rolled down his window, drew a 9 mm blue-steel pistol and fired at the Suburban; four bullets hit Wallace. Wallace's entourage rushed him to, where doctors performed an emergency, but he was pronounced dead at 1:15 a.m. He was 24 years old. His was released to the public in December 2012, fifteen years after his death. According to the report, three of the four shots were not fatal. The first bullet hit his left forearm and traveled down to his wrist; the second hit him in the back, missing all vital organs, and exited through his left shoulder; and the third hit his left thigh and exited through his inner thigh. The report said that the third bullet struck 'the left side of the scrotum, causing a very shallow, 3⁄ 8 inch 10 mm linear laceration.'

The fourth bullet was fatal, entering through his right hip and striking several vital organs, including his, and the upper lobe of his left, before stopping in his left shoulder area. Wallace's death was mourned by fellow hip hop artists and fans worldwide. Rapper felt at the time of Wallace's death that his passing, along with that of, 'was nearly the end of rap.' Investigation Immediately following the shooting, reports surfaced linking Wallace's murder with six months earlier, due to similarities in the drive-by shootings and the highly publicized East Coast–West Coast hip hop feud, of which Shakur and Wallace had been central figures. Media reports had previously speculated that Wallace was in some way connected to Shakur's murder, though no evidence ever surfaced to seriously implicate him. Shortly after Wallace's death, writers and Matt Lait reported that the key suspect in his murder was a member of the Southside Crips acting in service of a personal financial motive, rather than on the gang's behalf.

The investigation stalled, however, and no one was ever formally charged. In a 2002 book by, called LAbyrinth, information was compiled about the murders of Wallace and Shakur based on information provided by retired LAPD detective. In the book, Sullivan accused Suge Knight, co-founder of Death Row Records and a known Bloods affiliate, of conspiring with corrupt LAPD officer to kill Wallace and make both deaths appear to be the result of the rap rivalry. The book stated that one of Mack's alleged associates, Amir Muhammad, was the who killed Wallace. The theory was based on evidence provided by an and the general resemblance of Muhammad to the generated during the investigation. In 2002, filmmaker released a documentary, based on information from the book.

Described Broomfield's low-budget documentary as a 'largely speculative' and 'circumstantial' account relying on flimsy evidence, failing to 'present counter-evidence' or 'question sources.' Moreover, the motive suggested for the murder of Wallace in the documentary—to decrease suspicion for the Shakur shooting six months earlier—was, as The New York Times put it, 'unsupported in the film.' An article published in by Sullivan in December 2005 accused the LAPD of not fully investigating links with Death Row Records based on Poole's evidence. Sullivan claimed that Combs 'failed to fully cooperate with the investigation', and according to Poole, encouraged Bad Boy staff to do the same. The accuracy of the article was later challenged in a letter by the Assistant Managing Editor of the Los Angeles Times, who accused Sullivan of using 'shoddy tactics.' Sullivan, in response, quoted the lead attorney of the Wallace estate calling the newspaper 'a co-conspirator in the cover-up.'

In alluding to Sullivan and Poole's theory that formed the basis of the Wallace family's dismissed $500 million lawsuit against the City of Los Angeles, The New York Times wrote: 'A cottage industry of criminal speculation has sprung up around the case, with documentaries, books and a stream of lurid magazine articles implicating gangs, crooked cops and a cross-country rap rivalry,' noting that everything associated with Wallace's death had been 'big business.' More recently, a Hollywood film was produced based on the Poole's investigation and Sullivan's book:, starring as Poole, is scheduled to be released in 2018. In examining Sullivan's assertion that the Los Angeles Times was involved in a cover-up conspiracy with the LAPD, it is instructive to note that conflicting theories of the murder were offered in different sections of the Times. The Metro section of the Times wrote that police suspected a connection between Wallace's death and the, consistent with Sullivan and Poole's theory. The Metro section also ran a photo of Muhammad, identified by police as a mortgage broker unconnected to the murder who appeared to match details of the shooter, and the paper printed his name and driver's license.

But Chuck Philips, a staff writer for the Business section of the Times who had been following the investigation and had not heard of the Rampart–Muhammad theory, searched for Muhammad, whom the Metro reporters could not find for comment. It took Philips only three days to find Muhammad, who had a current ad for his brokerage business running in the Times. Muhammad, who was not an official suspect at the time, came forward to clear his name. The Metro section of the paper was opposed to running a retraction, but the business desk editor, Mark Saylor, said, 'Chuck is sort of the world's authority on rap violence' and pushed, along with Philips, for the Times to retract the article. The May 2000 Los Angeles Times correction article was written by Philips, who quoted Muhammad as saying, 'I'm a mortgage broker, not a murderer' and asking, 'How can something so completely false end up on the front page of a major newspaper?'

The story cleared Muhammad's name. A later 2005 story by Philips showed that the main informant for the Poole-Sullivan theory was a with admitted memory lapses known as 'Psycho Mike' who confessed to. John Cook of noted that Philips' article 'demolished' the Poole-Sullivan theory of Wallace's murder.

In the 2000 book, investigative journalist and author suggested that Wallace and Shakur's murders might have been the result of the East Coast–West Coast feud and motivated by financial gain for the record companies, because the rappers were worth more dead than alive. The criminal investigation into Wallace's murder was re-opened in July 2006 to look for new evidence to help the city defend the civil lawsuits brought by the Wallace family. Retired LAPD detective, who worked for three years on a gang task force that included the Wallace case, alleges that the rapper was shot by Wardell 'Poochie' Fouse, an associate of Knight, who died on July 24, 2003, after being shot in the back while riding his motorcycle in. Kading believes Knight hired Poochie via his girlfriend, 'Theresa Swann,' to kill Wallace to avenge the death of Shakur, who, Kading alleges, was killed under the orders of Combs. In December 2012, the LAPD released the autopsy results conducted on Wallace's body to generate new leads.

The release was criticized by the long-time lawyer of his estate, Perry Sanders Jr., who objected to an autopsy. The case remains officially unsolved. Lawsuits Wrongful death claim In March 2006, Wallace's mother Voletta filed a against the City of Los Angeles based on the evidence championed by Poole. They claimed the LAPD had sufficient evidence to arrest the assailant, but failed to use it.

David Mack and Amir Muhammad (a.k.a. Harry Billups) were originally named as defendants in the, but were dropped shortly before the trial began after the LAPD and dismissed them as suspects. The case came for trial before a jury on June 21, 2005.

On the eve of the trial, a key witness who was expected to testify, Kevin Hackie, revealed that he suffered memory lapses due to psychiatric medications. He had previously testified to knowledge of involvement between Knight, Mack, and Muhammed, but later said that the Wallace attorneys had altered his declarations to include words he never said. Hackie took full blame for filing a false declaration.

Several days into the trial, the plaintiffs' attorney disclosed to the Court and opposing counsel that he had received a telephone call from someone claiming to be a LAPD officer and provided detailed information about the existence of evidence concerning the Wallace murder. The court directed the city to conduct a thorough investigation, which uncovered previously undisclosed evidence, much of which was in the desk or cabinet of Det. Steven Katz, the lead detective in the Wallace investigation. The documents centered around interviews by numerous police officers of an incarcerated informant, who had been a cellmate of imprisoned Rampart officer for some extended period of time. He reported that Perez had told him about his and Mack's involvement with Death Row Records and their activities at the Peterson Automotive Museum the night of Wallace's murder. As a result of the newly discovered evidence, the judge declared a and awarded the Wallace family its attorneys' fees.

On April 16, 2007, relatives of Wallace filed a second wrongful death lawsuit against the City of Los Angeles. The suit also named two LAPD officers in the center of the investigation into the Rampart scandal, Perez. According to the claim, Perez, an alleged affiliate of Death Row Records, admitted to LAPD officials that he and Mack (who was not named in the lawsuit) 'conspired to murder, and participated in the murder of Christopher Wallace'. The Wallace family said the LAPD 'consciously concealed Rafael Perez's involvement in the murder of. Granted to the city on December 17, 2007, finding that the Wallace family had not complied with a California law that required the family to give notice of its claim to the State within six months of Wallace's death. The Wallace family refiled the suit, dropping the state law claims on May 27, 2008. The suit against the City of Los Angeles was finally dismissed in 2010.

It was described by The New York Times as 'one of the longest running and most contentious celebrity cases in history.' The Wallace suit had asked for $500 million from the city.

Defamation On January 19, 2007, a friend of Shakur who was implicated in Wallace's murder by the Los Angeles affiliate and in 2005, had a lawsuit regarding the accusations thrown out of court. See also.

References. March 12, 1997. Retrieved May 6, 2008. ^ Bruno, Anthony 2007-04-07 at the. Court TV Crime Library.

Retrieved January 24, 2007. ^ Sullivan, Randall (December 5, 2005). Rolling Stone. Archived from on April 29, 2009.

Retrieved October 7, 2006. Purdum, Todd S. (March 10, 1997). Retrieved February 23, 2009. nevereatshreddedwheat # (March 9, 1997). Retrieved December 31, 2013. Horowitz, Steven J.

(December 7, 2012). Retrieved December 7, 2012. Smith, Alex M. (August 18, 2014). Las Vegas Sun. Futura font family zip. March 10, 1997. Philips Laitt, Chuck Matt (March 18, 1997).

Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 18, 2013. ^ Fuchs, Cynthia (September 6, 2002). ' PopMatters. Retrieved January 2, 2007. ^ Serpick, Evan (April 12, 2002).

Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 2, 2007. ^ Philips, Chuck Los Angeles Times, February 7, 2007. Retrieved April 14, 2007. ^ Philips, Chuck (June 20, 2005). Retrieved October 3, 2013.

^ Leland, John (October 7, 2002). New York Times. Retrieved September 30, 2013. Duvoisin, Marc; Sullivan, Randall (January 12, 2006).

Rolling Stone. Archived from on August 17, 2007. Retrieved December 6, 2012. ^ SISARIO, Ben (April 19, 2010). New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

^ Cook, John (May 23–26, 2000). Brills Content. Archived from on 2012-08-09. Retrieved August 1, 2012. Trounson, Rebecca (February 22, 2012). Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

Philips, Chuck (May 3, 2000). Los Angeles Times. ^ Cook, John. Reference tone. Retrieved September 7, 2013. Philips, Chuck (June 3, 2005). Retrieved September 15, 2013.

Bruno, Anthony. Archived from on 2013-11-10. Retrieved December 31, 2013. Philips, Chuck (July 31, 2006).

Los Angeles Times. Archived from on October 21, 2006.

Retrieved January 20, 2007. Associated Press. August 3, 2006.

Retrieved September 29, 2006. Kenner, Rob (March 9, 2012). Retrieved September 26, 2012. Quinn, Rob (October 4, 2011). Retrieved September 26, 2012.

Wolfe, Roman (December 8, 2012). Retrieved December 9, 2012. Estate of Wallace v. City of Los Angeles, 229 F.R.D. 2005);Reid, Shaheem (July 5, 2005). Retrieved February 14, 2007.

Finn, Natalie (April 18, 2007). Retrieved August 2, 2007.

Estate of Christopher G.L. City of Los Angeles, et al., 2:07-cv-02956-FMC-RZx, slip op. December 17, 2007) (Cooper, J.). Complaint, Estate of Christopher G.L.

City of Los Angeles, et al., 2:07-cv-02956-FMC-RZx (C.D. May 27, 2008). Associated Press. January 20, 2007.

Retrieved August 2, 2009.

Wallace attended the before transferring out at his own request At Queen of All Saints Middle School, Wallace excelled, winning several awards as an English student. He was nicknamed 'Big' because of his overweight size by age 10.

He said he started when he was around the age of 12. His mother, often away at work, did not know of his drug dealing until he was an adult. Wallace began as a teenager, entertaining people on the streets and performed with local groups the Old Gold Brothers and the Techniques. At his request, Wallace transferred from to, where future rappers, and were also attending. According to his mother, Wallace was still a good student but developed a 'smart-ass' attitude at the new school. At seventeen, Wallace dropped out of school and became more involved in crime. In 1989, he was arrested on weapons charges in Brooklyn and sentenced to five years' probation.

In 1990, he was arrested on a violation of his probation. A year later, Wallace was arrested in for dealing. He spent nine months in jail before making bail. 1991–1994: Career beginnings and first child After being released from jail, Wallace made a under the name Biggie Smalls, a reference to a character in the 1975 film as well as his stature; he stood at 6 feet 3 inches (1.91 m) and weighed 300 to 380 lb (140–170 kg) according to differing accounts. The tape was reportedly made with no serious intent of getting a recording deal. However, it was promoted by New York-based DJ, who had previously worked with, and in 1992 it was heard by the editor of. In March 1992, Wallace was featured in The Source 's Unsigned Hype column, dedicated to aspiring rappers, and made a recording off the back of this success.

The demo tape was heard by and record producer, who arranged for a meeting with Wallace. He was signed to Uptown immediately and made an appearance on label mates 's 'A Buncha Niggas' (from the album ). Soon after Wallace signed his recording contract, Combs was fired from Uptown and started a new label,.

Wallace followed and signed to the label in mid-1992. On August 8, 1993, Wallace's longtime girlfriend gave birth to his first child, T'yanna. Wallace had split with the girlfriend some time before T'yanna's birth. Despite having dropped out of high school himself, Wallace wanted his daughter to complete her education. He promised her 'everything she wanted', saying that if his mother had promised him the same he would have graduated at the top of his class. He continued selling drugs after the birth to support his daughter financially.

Once Combs discovered this, he forced Wallace to quit. Later in the year, Wallace, recording as the Notorious B.I.G., gained exposure after featuring on a remix to 's single '. He recorded under this name for the remainder of his career, after finding the original moniker 'Biggie Smalls' was already in use. 'Real Love' peaked at No. 7 on the chart and was followed by a remix of Blige's '. He continued this success, to a lesser extent, on remixes with ('Buddy X') and artist ('Dolly My Baby', also featuring Combs) in 1993. In April 1993, his solo track, ', appeared on the soundtrack.

In July 1994, he appeared alongside and Busta Rhymes on a remix to label mate 's ', which reached No. 1994: Ready to Die and marriage. Main article: In February 1997, Wallace traveled to California to promote Life After Death and record a music video for its lead single, '. On March 5, 1997, he gave a radio interview with on in San Francisco. In the interview, he stated that he had hired a security detail, since he feared for his safety; this was because he was a celebrity figure in general, not because he was a rapper. On March 8, 1997, Wallace presented an award to at the 11th Annual in Los Angeles and was booed by some of the audience. After the ceremony, he attended an afterparty hosted by and at the in Los Angeles.

Guests included Evans, Combs, and members of the and gangs. On March 9, 1997, at 12:30 a.m. , after the fire department closed the party early due to overcrowding, Wallace left with his entourage in two to return to his hotel. He traveled in the front passenger seat alongside his associates, Damion 'D-Roc' Butler, Lil' Cease and driver Gregory 'G-Money' Young. Combs traveled in the other vehicle with three bodyguards. The two trucks were trailed by a carrying Bad Boy's director of security, Paul Offord.

By 12:45 a.m. (PST), the streets were crowded with people leaving the party. Wallace's truck stopped at a red light 50 yards (46 m) from the museum. A black pulled up alongside Wallace's truck. The driver of the Impala, an African-American male dressed in a blue suit and bow tie, rolled down his window, drew a 9 mm blue-steel pistol and fired at the GMC Suburban. Four bullets hit Wallace.

His entourage rushed him to, but he was pronounced dead at 1:15 a.m. Wallace's funeral was held on March 18, 1997, at the in. There were among 350 mourners at the funeral, including, Lil' Cease, and others. After the funeral, his body was cremated and the ashes were given to his family. Posthumous releases Sixteen days after his death, Wallace's double-disc second album was released as planned with the shortened title of and hit No. 1 on the charts, after making a premature appearance at No. 176 due to street-date violations.

The record album featured a much wider range of guests and producers than its predecessor. It gained strong reviews and in 2000 was certified, the highest certification awarded to a solo hip hop album. Its lead single, ', was the last music video recording in which Wallace would participate.

His biggest chart success was with its follow-up ', featuring Sean Combs (under the rap alias '). Both singles reached No. 1 in the Hot 100, making Wallace the first artist to achieve this feat posthumously. The third single, ', featuring the band 112, was noted for its use of children in the music video, directed by, who were used to portray Wallace and his contemporaries, including Combs, Lil' Kim, and Busta Rhymes. Wallace was named Artist of the Year and 'Hypnotize' Single of the Year by magazine in December 1997. In mid-1997, Combs released his debut album, which featured Wallace on five songs, notably on the third single '. The most prominent single from the record album was ', featuring Combs, Faith Evans and 112, which was dedicated to Wallace's memory.

At the 1998, Life After Death and its first two singles received nominations in the rap category. The album award was won by Combs' No Way Out and 'I'll Be Missing You' won the award in the category of Best Rap Performance By A Duo Or Group in which 'Mo Money Mo Problems' was nominated. In 1996, Wallace started putting together a hip hop, the Commission, which consisted himself, Jay-Z, Combs,.

The Commission was mentioned by Wallace in the lyrics of 'What's Beef' on and ' from, but a Commission album was never completed. A track on Duets: The Final Chapter, 'Whatchu Want (The Commission)', featuring Jay-Z, was based on the group. In December 1999, Bad Boy released. The album consisted of previously unreleased material mixed with new guest appearances, including many artists Wallace had never collaborated with in his lifetime. It gained some positive reviews, but received criticism for its unlikely pairings; The Source describing it as 'compiling some of the most awkward collaborations of his career'.

Nevertheless, the album sold 2 million copies. Wallace appeared on Michael Jackson's 2001 album,.

Over the course of time, his vocals were heard on hit songs such as ' and 'Realest Niggas' by in 2002, and the song ' with Shakur the following year. In 2005, continued the pattern started on Born Again, which was criticized for the lack of significant vocals by Wallace on some of its songs. Its lead single ' became Wallace's first UK No. Combs and Voletta Wallace have stated the album will be the last release primarily featuring new material. A duet album, featuring Evans and Notorious B.I.G., was released on May 19, 2017, which largely contained previously unreleased music. Musical style.

Wallace tells vivid stories about his everyday life as a criminal in (from ). Problems playing these files? Wallace mostly rapped on his songs in a deep tone described by Rolling Stone as a 'thick, jaunty grumble', which went deeper on Life After Death. He was often accompanied on songs with from Sean 'Puffy' Combs.

In The Source 's Unsigned Hype column, his style was described as 'cool, nasal, and filtered, to bless his own material'. AllMusic describe Wallace as having 'a talent for piling multiple rhymes on top of one another in quick succession'.

Time magazine wrote Wallace rapped with an ability to 'make sound. Smooth', while Krims describes Wallace's rhythmic style as 'effusive.' Before starting a verse, Wallace sometimes used to 'warm up' (for example 'uhhh' at the beginning of 'Hypnotize' and 'Big Poppa', and 'whaat' after certain rhymes in songs such as 'My Downfall'). Of notes that Wallace had, 'intense and complex flows', of says, 'Biggie was a master of the flow', and states that Wallace mastered 'all the hemispheres of the music'. He also often used the single-line to add variety and interest to his flow. Suggests that Wallace didn't need a large vocabulary to impress listeners – 'he just put his words together a slick way and it worked real good for him'.

Wallace was known to compose lyrics in his head, rather than write them down on paper, in a similar way to. Wallace would occasionally vary from his usual style. On 'Playa Hater' from his second album, he sang in a slow. On his collaboration with, ', he modified his style to match the rapid rhyme flow of the group.

Themes and lyrics Wallace's lyrical topics and themes included tales ('Niggas Bleed'), his drug dealing past ('10 Crack Commandments'), materialistic bragging ('), as well as humor ('Just Playing (Dreams)'), and ('Me & My Bitch'). Rolling Stone named Wallace in 2004 as 'one of the few young male songwriters in any pop style writing credible love songs'., in the book, describes how Wallace was able to both 'glorify the upper echelon' and 'make you feel his struggle'. According to of in 1994, Wallace's lyrics 'mixed autobiographical details about crime and violence with emotional honesty'. Marriott of The New York Times (in 1997) believed his lyrics were not strictly autobiographical and wrote he 'had a knack for exaggeration that increased sales'. Wallace described his debut as 'a big pie, with each slice indicating a different point in my life involving bitches and niggaz.

From the beginning to the end'. Ready to Die is described by as a contrast of 'bleak' street visions and being 'full of high-spirited fun, bringing the pleasure principle back to hip-hop'.

AllMusic write of 'a sense of doom' in some of his songs and the NY Times note some being 'laced with paranoia'; Wallace described himself as feeling 'broke and depressed' when he made his debut. The final song on the album, ', featured Wallace contemplating suicide and concluded with him committing the act. On, Wallace's lyrics went 'deeper'. Krims explains how upbeat, dance-oriented tracks (which featured less heavily on his debut) alternate with ' songs on the record and suggests that he was 'going pimp' through some of the lyrical topics of the former. Wrote that Wallace 'revamped his image' through the portrayal of himself between the albums, going from 'midlevel hustler' on his debut to '. AllMusic wrote that the success of Ready to Die is 'mostly due to Wallace's skill as a storyteller'; in 1994, Rolling Stone described Wallace's ability in this technique as painting 'a sonic picture so vibrant that you're transported right to the scene'.

On Life After Death, Wallace notably demonstrated this skill on 'I Got a Story to Tell', creating a story as a rap for the first half of the song and then retelling the same story 'for his boys' in conversation form. A stencil of the Notorious B.I.G. In (2006) Considered one of the best rappers of all time, Wallace was described by as 'the savior of East Coast hip-hop'. Magazine named Wallace the greatest rapper of all time in its 150th issue in 2002. In 2003, when asked several hip hop artists to list their five favorite, Wallace's name appeared on more rappers' lists than anyone else. In 2006, ranked him at No. 3 on their list of The Greatest MCs of All Time, calling him possibly 'the most skillful ever on the mic'.

Editors of ranked him No. 3 on their list of the Top 50 MCs of Our Time (1987–2007). In 2012, The Source ranked him No.

3 on their list of the Top 50 Lyrical Leaders of all time. Rolling Stone has referred to him as the 'greatest rapper that ever lived'. In 2015, Billboard named Wallace as the greatest rapper of all time. Since his death, Wallace's lyrics have been sampled and quoted by a variety of hip hop, R&B and pop artists including Jay-Z,.

On August 28, 2005, at the 2005, Sean Combs (then using the rap alias 'P. Diddy') and paid tribute to Wallace: an orchestra played while the vocals from ' and ' played on the arena speakers. In September 2005, held its second annual 'Hip Hop Honors', with a tribute to Wallace headlining the show. Wallace had begun to promote a clothing line called Brooklyn Mint, which was to produce plus-sized clothing but fell dormant after he died. In 2004, his managers, Mark Pitts and Wayne Barrow, launched the clothing line, with help from Jay-Z, selling T-shirts with images of Wallace on them. A portion of the proceeds go to the Christopher Wallace Foundation and to Jay-Z's Shawn Carter Scholarship Foundation. In 2005, Voletta Wallace hired branding and licensing agency Wicked Cow Entertainment to guide the estate's licensing efforts.

Wallace-branded products on the market include action figures, blankets, and cell phone content. The Christopher Wallace Memorial Foundation holds an annual black-tie dinner ('B.I.G. Night Out') to raise funds for children's school equipment and to honor Wallace's memory. For this particular event, because it is a children's schools' charity, 'B.I.G.' Is also said to stand for 'Books Instead of Guns'. There is a large portrait mural of Wallace as on Fulton Street in Brooklyn a half-mile west from Wallace's old block. A fan petitioned to have the corner of Fulton Street and St.

Big Notorious Death Video

James Place, near Wallace's childhood home renamed in his honor, garnering support from local businesses and attracting more than 560 signatures. A large portrait of Wallace features prominently in the series, due to the fact that he served as muse for the creation of the 's version of character. Biopic is a 2009 about Wallace and his life that stars rapper as Wallace. The film was directed by and distributed. Producers included Sean Combs, Wallace's former managers Wayne Barrow and Mark Pitts, as well as Voletta Wallace.

On January 16, 2009, the movie's debut at the Grand 18 theater in Greensboro, North Carolina was postponed after a man was shot in the parking lot before the show. The film received mixed reviews and grossed over $44 million worldwide. In early October 2007, open casting calls for the role of Wallace began.

Actors, rappers and unknowns all tried out. Auditioned for the role, but was not picked. Claimed that he would play the role of Wallace, but producers denied it. Eventually, it was announced that rapper Jamal Woolard was chosen to play Wallace while Wallace's son, Christopher Wallace, Jr. Was cast to play Wallace as a child. Other cast members include as Voletta Wallace, as, as, as, and as.

Bad Boy also released a to the film on January 13, 2009; the album contains many of Wallace's hit singles, including 'Hypnotize' and 'Juicy', as well as rarities. Main article: Studio albums. (1994).

(1997) Collaboration albums. (with ) (1995) Posthumous studio albums. (1999). (2005) Posthumous collaboration albums.

Big Notorious Death Photos

(with ) (2017) Media Filmography. (1995) as himself. Ryme & Reason (1997 (1997) as himself. (2004) archive footage. (2009) archive footage.

B I G Notorious Songs

(2017) archive footage Television appearances. New York Undercover (1995) as himself. Martin (1995) as himself. Who Shot Biggie & Tupac? (2017). (2018) Awards and nominations Award Year of ceremony Nominee/work Category Result 1995 The Notorious B.I.G. Rap Artist of the Year Won ' Rap Single of the Year Won ' Nominated ' Best Rap Solo Performance Nominated ' (with and ) Nominated Nominated ' Won 'Mo Money Mo Problems' (with Mase and Puff Daddy) Best Rap Video Nominated 1998 Life After Death Best R&B/Soul Album, Male Won 'Mo Money Mo Problems' (with Mase and Puff Daddy) Best R&B/Soul Album Nominated Best R&B/Soul or Rap Music Video Nominated References.